I was recently invited to give a short presentation to the California Land Equity Task Force. The state-appointed body is made up of 13 appointed members that represent a diversity of agricultural interests across the state, supported by staff members of the California Strategic Growth Council. The main mandate of the Task Force is to offer “recommendations on how to address the agricultural land equity crisis.” These recommendations will be submitted to the California Legislature and Governor.

The case of the Task Force is an important one to follow. I’m not sure of any other state appointed groups that focus on land equity in the United States. I will be following the process and am curious to what policy recommendations the Task Force makes as well as how they are received by the CA legislature and Governor’s Office.

For the presentation, I was asked to prepare a briefing document about the drivers that lead to agricultural land consolidation and examples of known interventions into land markets—both in the US and further afield. Here is what I came up with: An introduction into the nuts of bolts of property, why agricultural consolidation comes about, and a survey of existing land market interventions. The survey of existing policy reminds us that, if we want to, we can legislate land.

Important Disclaimer: This report was shared with the California Agricultural Land Equity Task Force for informational purposes only and does not reflect an endorsement by or coordination with the Task Force or the State of California

The private property framework, why it leads to consolidation, and examples of land market interventions from around the world

Big picture

Property is a social relation, something made “real” through layers of legal precedent, institutional practice, and cultural acceptance.

The property system was designed to encourage certain forms of land use and benefit certain forms of land users over others.

Markets for land sit atop a form of the property relation knows as “the ownership model.”

The entrenched nature of the ownership model may explain why land equity actions focus overwhelmingly on access to the current property system, rather than challenging the rules of the property system.

The ownership model facilitates trends in monopoly formation, competition amongst owners over collaboration, an incentive to degrade the land, and financialization.

Despite the apparent naturalness of the ownership model, there are cases where it is challenged, tweaked and amended in the US.

Looking outside the US, but still in industrialized countries with strong constitutional commitments to property, we can see more direct examples of legislative challenges to the ownership model.

Within a survey of land market interventions prepared in this document, approaches coalesce around public interest tests, size caps, first right of refusal or “right to buy”, land use restrictions, and exclusion of certain owner types.

Because the legislative process is daunting, the establishment of a Land Commission and Land Observatory are strategies to build support for legislative change.

One should expect the boundaries of property to be rigidly defended.

Introduction

In pursuit of land equity, there are three overarching strategies. The most popular strategy is to try to get the existing owners of property to be less exploitative in their use. This strategy, focuses on providing more access to farmland, but does not upset ownership or control. Second, there are efforts to re-allocate property rights to a new coalition of users that might behave differently with their ownership. This strategy implies some form of redistribution or land ownership diversification. Finally, we see a less favored strategy that try to create a new way the system of property works, such that it resists a slide towards consolidation, monopolies, and minority control. This background document focuses on the second and third strategies, efforts that directly challenge the current ownership structure.

The nuts and bolts of property and the rise of the “ownership model”

Property is often taken as something settled or natural, but it is a human concept full of contradictions. Property is made real through the interaction between individuals and state power[i]. Thus, it is useful to think of property as a social relation rather than a relationship between a person and a material thing.

Historians of property have connected its design to ideological visions of economic and civic structure[1]. For some, strong property rights are the pillar of freedom, where defense of an individuals’ right to own things is the only way to ward off an authoritarian state and to ensure that entrepreneurs can reliably benefit from their investments[2]. For others, the origins of property point towards a strategy to formalize enclosure, assert a domination of humans over nature, and signal a way to profit off of materials previously held in common[3]. As Carol Rose writes:

The doctrine of first possession, [...]reflects the attitude that humans are outsiders to nature. It gives the earth and its creatures over to those who mark them so clearly as to transform them, so that no one will mistake them for unsubdued nature. The metaphor of the law of first possession is, after all, death and transfiguration; to own a fox the hunter must slay it, so that he or someone else can turn it into a coat. (p. 18)

Out of all of the potential ways to organize property, one particular form has risen to dominance in the so-called Global North. Property scholars track the rise of the “ownership model” of property, where the entitlements of individual owners are favored over public interests[4].

The ownership model is summarized as: “[P]roperty to which the following can be attached: To the world, ‘Keep off unless you have my permission, which I may grant or withhold’. Signed: private citizen. Endorsed: The State” (p. 3)[5].

The legal basis for the ownership model of property

In the US, there are bedrock legal commitments to property the entrench the ownership model. The Fifth Amendment of the constitution indicates: “[…] nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”[6] and the Fourteenth Amendment says: “[…] nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”[7] Article 1, Protocol 1 of European Convention on Human Rights states “Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions,” equating the right to property as a human right.

The heart of the ownership model are state backed rights of acquisition, exclusive use, and “disposal” (sale, gifting, transfer) of property. If we apply this agriculture, the owner of farmland can choose how to manage the land within the boundary of their parcel even if it affects neighbors, eaters, future generations, or downstream users. The owner has the exclusive right to decide who becomes a tenant, regardless of their capacity or values. Most importantly for this document, the owner can determine when to transfer the land, set the price, and choose whom to sell it to.

In practice, absolute rights to acquire, exclusively use and dispose are blunted by a variety of other legal commitments. Police powers like zoning, nuisance law, tort law (claims between private citizens), and the doctrine of the public trust are examples of legal structures that complicate the place of property in society. The government can assert eminent domain to rearrange property allocations in pursuit of a state interest. Some, think that such government infringements on the ownership model are unjustly restrictive on an individual right to property and wish to see a deepening of the ownership model. Such legal thought has called the effort to strengthen property rights against state intervention the “civil rights issue of our time.” (Marzulla 2001, 241)

The Cato institute’s Handbook for policy makers: Property rights and the constitution concludes:

The Founders would be appalled to see what we have done to property rights over the course of the 20th century. [..] The time has come to restore respect for these most basic of rights, the foundation of all of our rights. Indeed, despotic governments have long understood that if you control property, you control the media, the churches, the political process itself.[8]

The meaning of property is deeply political. Its contested nature suggests that remaking property is much more than a legal endeavor. The property system represents a powerful expression of values about human relationships to land.

How land markets work in the US property context:

An unregulated land market implies few, if any, limitations on the way land changes hands. In a fully unregulated market (one where the ownership model of property is dominant) an owner of farmland can sell the land to any recipient. The owner can set the price as they choose. They can sell the land without any public review, for example, outside any register of pending sales. There is no time limitations or requirement for public notification. Finally, the new owner can change the land use to their liking.

The ownership model of property has observable outcomes relevant to land markets[9]. The ownership model:

Encourages a self-interested competition, where the most benefit come from maximizing productivity of what an individual owns;

Facilitates monopoly formation, as the least profitable from this competition go bankrupt and sell their property to others;

Preserves wealth from the original acquisition of property;

Sets up a tension between the state who is supposed interests are everybody in its jurisdiction and a minority of those who own the productive materials that generate wealth;

Allocates political power to those who own things versus those who don’t.

When these dynamics of the ownership model are applied to farmland, it drives predictable outcomes of agribusiness consolidation, financialization, land quality depletion, unequal wealth distribution, and competition; all things crucial for the future of agriculture[10].

Consolidation comes about in part through logics of market competition. The profit-driven nature of agriculture incentivizes farm consolidation, as competitive pressures favor the most cost-efficient producers, leading to the gradual displacement of less competitive farmers. This cycle persists as successful farmers, seeking to expand their operations, acquire land from struggling farmers—often through debt financing—ultimately driving the sector toward fewer, larger farms and reinforcing a system of intensified production with diminishing returns.[11], [12]. Original allocation of property rights in the US through legacies of indigenous dispossession and slavery entrenches a racialized wealth distribution[13]. After the 2008 financial crisis, financial actors saw farmland as a “safe” investment that would reliably offer steady returns, and farmland became a popular portion of hedge fund, endowment, and retirement fund portfolios[14], [15] .

Therefore, if one wants to create equity within agricultural land, one might need to disrupt the ownership model, which acts as the underlying driver of the problems mentioned[16]. There is therefore an important distinction between trying to redistribute access within a unified understanding of property compared to trying to remake the rules of property so that redistribution subsequently occurs.

The state of farmland ownership in California

Land ownership is public information, available through tax assessor records. However, data providers may be incapable of delivering geo-spatial land ownership data in an easy-to-interpret format, may withhold for fear of certain privacy concerns, or fail to reveal a clear picture of actual ownership patterns that are obfuscated by different ownership entities. That said, a national survey of farmland ownership in completed in the 2012 agricultural census revealed important benchmarks and is the last national survey focused on agricultural land tenure[17].

The highlights of this report is that 40% of California farmland is rented out, 81% is owned by non-operator landlords. Land classified as “family owned” accounts for close to 80% of CA farmland, where the USDA classifies trusts, corporations and partnerships making up the other 20%. Further analysis shows that the largest 5% of properties make up 50% of cropland; which means the remaining 95% are small properties and constitute the other half of ag land[18]. Since the last land tenure survey, inquiries into land ownership change do indicate a shift towards more corporate or non-individual ownership. A study of land ownership change between 2003 and 2017 in San Joaquin Valley showed that, on average, limited liability companies (LLCs) bought 5.7 times as many acres of farmland across the state (192 acres) compared to individual buyers (34 acres), and 6.9 times as many acres as the average individual buyer in over-drafted basins[19].

Examples of land market interventions from around the world

At the heart of the ownership model is the state guarantee of an individual right to acquire, exclusively use, and dispose of property. Thus interventions into the status quo disrupt one or more of these three things. When survey existing policy options to provide land access, it is useful to track if and how they intervene in the ownership model. For example, a recent national survey of “bipartisan” land access policy in the US exclusively focused on tax incentives and other funding mechanisms. While useful, none of these policies intervened in the logics of the property system, highlighting the difference between land access and land market policy options[20]. Therefore, this document focuses on exploring both inside and outside the US for a broader diversity of land market interventions (Table 1).

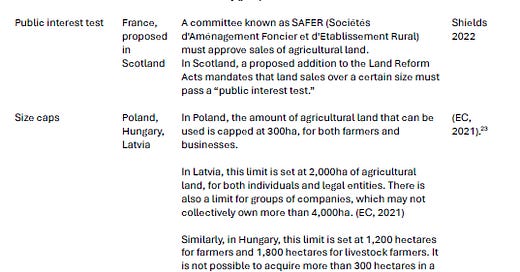

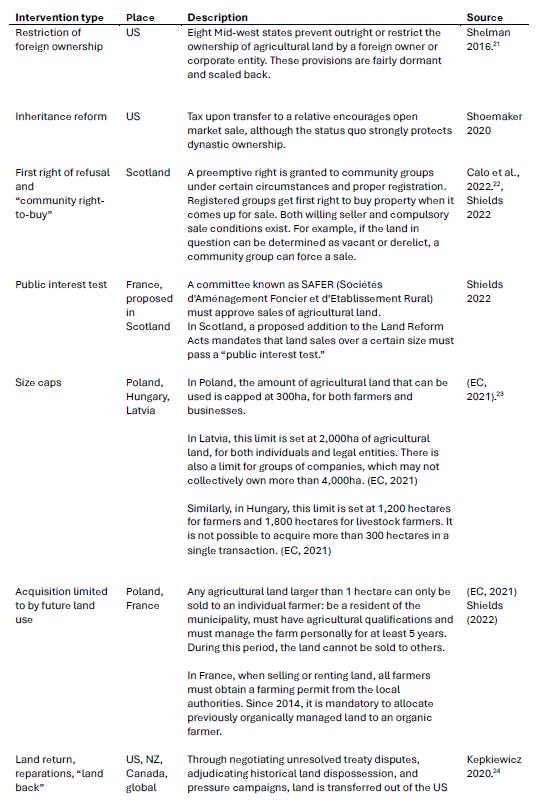

Table 1. Highlights of land market interventions

Sources for the table ( Shelman 2016[21], Calo et al., 2022[22], Shields 2022, (EC, 2021)[23], Oldham 2024[25], Oh 2023[26] ,ECVC 2023[27]

Land market interventions and the boundaries of legality

Many of the examples highlighted intervene at the point of sale of land. In other terms, these interventions challenge the “right to dispose” element of property norms. These type of interventions are rare (especially in the US) because they run the risk of legal challenge through principles such as the European Convention of Human Rights (UNCHR) and US case law. Although, there is a growing attention to how the right to property has been successfully balanced by competing legal priorities within a braider survey of case law that focuses on contest land use[28]. For example, the Scottish Land Reform Acts asserted that the government had the right balance a right to property guaranteed by the UNCHR because of commitments to the UN declaration on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. The legal argument was that a state may need to infringe on individual property rights to secure public goods.

Critical legal studies stress that legal interpretation and broader politics shape the determined appropriateness of any legal ruling much more so than careful doctrinal analysis. Recent cases and case law indicate that property rights can be unwound, retrenched, or rethought.

Unwound: In Held v. Montana (2023), a state constitutional guarantee to a “clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations” created an opportunity for a youth climate advocacy group to file suit against the states approach to fossil fuel exploration. This ruling suggests that the interests of property can be balanced against commitments to the public trust.

Retrenched: The Supreme Court ruling in Cedar Point Nursery vs Hassid (2021) asserted that state mandated visitation to farmworkers by union organizers was in fact a violation of farmland owners’ private property. This case shows a legal entrenchment of the ownership model.

Rethought: While Flannery Associates used the power of the ownership model to amass significant agricultural property in the California Forever project, changing existing zoning laws to convert land into urban development has been, for now, stalled by democratic means[29].

Finally, there are two relevant bills introduced to the US Senate by Senator Cory booker: The Justice for Black Farmers Act and the Farmland for Farmers Act. The former proposes a land fund to purchase farmland and prioritize sale to Black farmers with favorable mortgage terms and the latter proposes restricting farmland ownership amongst certain corporate structures.

Conclusion

How can we transform the way our land is used? Creating more access to land for those excluded to the benefits of farmland is a clear priority. Few contest the goal of providing more access to the existing property system[ii]. A deeper challenge is one that tries to rewrite the rules of farmland ownership, control, and transfer. Such work may require careful intervention into the legal, institutional, and cultural commitments to property.

References

[i] Here, I note that the establishment of a property system is central to the legitimacy of the state itself. In settler colonies, the state in question is often an ethnostate, where a dominant group is favored to acquire property and enjoy state protection of that property (See Kedar, Alexandre S. 2012. “On the Legal Geography of Ethnocratic Settler States: Notes Towards a Research Agenda.” Law and Geography 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199260744.003.0020.).

[ii] It is important to recognize that for those long excluded from the great wealth and security of owning land, redistribution of property may be preferred over transformation of property’s rules. See Albertus, Michael. 2025. Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn’t, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies. New York: Basic Books.

Thanks Adam. Fascinating reminder that wired into our DNA is the desire to own, in its many manifestations and consequences. It’s a problem.

Interesting, thanks. I can add that in Sweden there is legislating prohibiting companies, funds etc from buying agriculture or forest land (although, those owning land before that law came into place can continue to own it and sell it to other legal persons). There are move to change this with the argument that there is a need for more capital in the ag sector (as farms have become so big and therefore so expensive).

I just wrote an op-ed in Swedish arguing for a land reform in Swedish forests to convert more of it into locally managed commons...