In the latest episode of Landscapes, researchers Lindsay Shade and Karen Rignall alerted me to Appalachian Land Ownership Survey of 1978. The project founders had a simple goal: figure out who owned the land in regions where they lived and worked, so that they had a starting point to make appeals to the correct individuals and corporate entities. According the Shade and Rignall, the project has a lasting impact in the region, acting as a progenitor of decades of civil society activism and democratic action regarding the region’s land use decisions.

At the end of the episode, when I asked Shade and Rignall about their leading ideas to ensure that an energy transition in Appalachia would be a just one, they returned to this idea of monitoring land ownership and land transfer:

Karen Rignall: Land ownership and transfer transparency is also important because the current owners and the actors who do have access to land ownership information really play the advantage.

So often you will see patterns of land transfers that happen in the lead up to a highway construction project. Well, some actors were given the heads up about the project, bought the land, and then turn it around for substantial profit, knowing that that project is going to be happening. There are numerous cases that have come to our attention around that.

So it really is also about positioning advocates, residents, with the information that others already have and are taking advantage of.

Why is understanding who owns what such a radicalizing and important task?

Land ownership affords economic, social, and political power that extends beyond the boundaries of any given parcel. It determines who captures value from development, who has a voice in planning, and who can leverage land as collateral for credit or political influence.

When communities become aware of stark inequalities in land ownership, it often ignites collective action. Frustration grows when people realize they cannot control the land they depend on for housing, livelihoods, or cultural identity. That frustration can become a powerful political force—binding together coalitions that might otherwise remain fragmented.

Meanwhile, powerful actors exploit opacity. They use obscurity in land registries and ownership structures to make speculative deals, secure rents, and extract profits—often at the expense of local communities. Flipping that dynamic through transparency is a proven tactic: when advocates and residents know who owns what, they can organize, negotiate, and hold decision-makers accountable with evidence-based claims.

That is why there are number of groups calling for institutionalizing land observatories, not as a one-off research project, but as a permanent public service.

With Meredith Song of UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, we’ve made this case in a new Op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle: Who controls California farmland? The hard-to-find answer is disturbing

In the article, we lay out a case for establishing a state-led Land Observatory as an antidote the rising problems of farmland consolidation and financialization of the agricultural system.

A land observatory on the national agenda

Our piece builds on recent calls for a state commitment to a land observatory that have bubbled up recently. Calls for a land observatory as a key tool to reform food systems has appeared in:

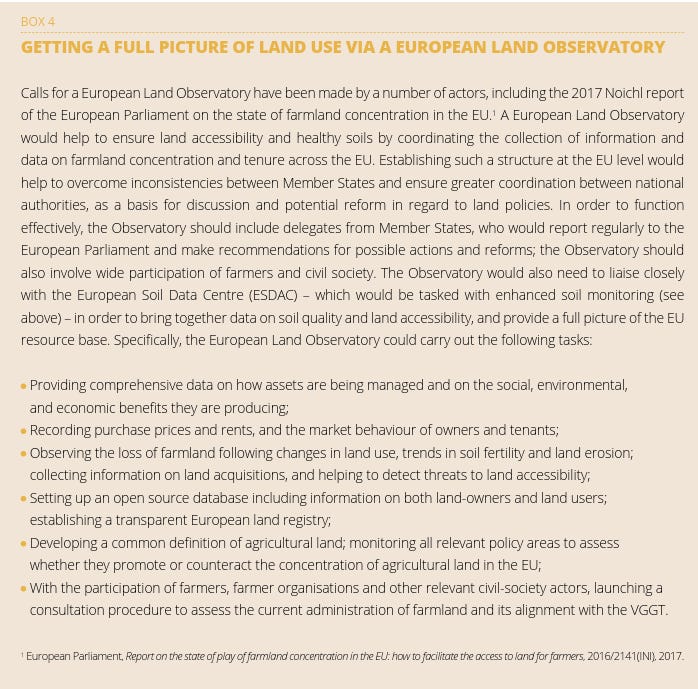

In IPES-Food’s report Towards a Common Food Policy for the EU

The EU Land Directive proposal from the European Coordination of La Via Campesina

Most recently, the European Union has announced a €1 million investment to pilot a Land Observatory for Europe.

As this policy idea gains traction, it is important to discuss it’s possible pitfalls. As a policy brief developed by the Transnational Institute and the European Access to Land Network notes:

The Land Observatory can either simply document the status quo or serve as a tool for policy innovation and reform to promote greater diversity and resilience in EU agriculture.

That is to say, while measuring land ownership trends may have spinoff benefits, the chance to create a powerful capacity to act on these data is an important policy struggle to wage.

Ensuring a farmland observatory has impact and democratic oversight

What is unique about the Appalachian Land Survey story is how the effort to map land ownership was always in service of enacting deep change in the regions use and access of land. There was an embedded goal of using knowledge to transform the region via strengthened appeals to powerful actors. The risk of making Land Observatories a state project is they may lose their transformative potential, becoming a mapping effort rather than a key pillar of land reform. Therefore, it’s important to lay out some principles for what a Land Observatory ought to do and how it ought to be structured.

The key tasks of a land observatory should be to assess not just ownership, but to leverage these and other land use data into a powerful new governance institution.

Beyond Ownership: The Full Picture

Ownership is only one layer. A Land Observatory ought to understand tenure—how many farmers rent the land they work, under what conditions, and at what cost. These details shape who bears risk, who captures value, and who has the ability to invest in long-term stewardship. Without this, we miss the material realities that determine the structure of agricultural sustainability.

Linking ownership → land use

Who owns the land influences what is grown and under what ecological conditions. A Land Observatory should track these relationships to reveal how ownership changes shape food systems and landscapes. Are new owners prioritizing monocultures or regenerative practices? Are shifts in ownership accelerating soil degradation or supporting biodiversity? These are the questions that connect land policy to climate and food system resilience.

Representation across the food system

A Land Observatory should not be a technocratic tool. It must be governed democratically, with representation from farmers, farmworkers, eaters, and citizens to ensure accountability and legitimacy. Food policy councils are a good example for how to structure these bodies and could even be tasked with running the policy dimension of the Land Observatory. Without this, the Observatory risks becoming a passive data repository.

Investigation for action

The Observatory should have a mandate to investigate anomalies—such as sudden spikes in land concentration or the rise of opaque ownership structures—and cut through shell company obscurity to identify real beneficiaries. This investigative capacity is essential to prevent land grabs and speculative bubbles that undermine rural economies. The Observatory must be equipped with state power to trigger policy responses when red flags appear.

Serve agroecology and renewal

Findings must inform policies that promote agroecological production, generational renewal, and a just food transition. That means using evidence to design incentives for young farmers, protect soils, and reduce dependence on extractive models of agriculture. These values ought to be explicit. The Observatory should be a cornerstone of a broader strategy to align land governance with climate and food system goals.

Open data for collective power

The data must be public, accessible, and usable so that diverse groups—grassroots organizations, researchers, journalists—can analyze, organize, and act. Open data democratizes knowledge and levels the playing field between communities and powerful actors.

A Final Word

We’ve laid out this vision in more detail in our recent San Francisco Chronicle op-ed—please give it a read. The central point is simple: without clear information on who controls farmland, it becomes difficult to design effective policies or maintain democratic oversight of land use.

Nice piece here. I'll have to check out the full article, but I absolutely agree that land ownership is key to addressing issues of environmental degradation. If it's collective, there's simply a much greater probably of its use being for the collective good.

Sorry pressed wrong button!

To conclude we are now reducing the amount of land that is farmed. We already import c.40% of our food. So in effect the UK is also exporting any environmental damage caused by that imported food. That is a case of out of sight out of mind. Nether does it make it any easier to influence growing methods or animal welfare. Neither does it ensure good working conditions and pay for those often poorer producers.

Politicians effectively only care about there being food on the supermarket shelves. Then when a disruption to food supplies occurs - such as a Covid outbreak for example - government panics only to discover that the levers they can pull are mostly ineffective nor immediate. But the real problem is that that scare is quickly forgotten.

I am reminded of a Chinese proverb:

“A man with a full stomach has many problems. A man with an empty stomach has one!”