Should we ask philanthropy to buy land for agroecology?

Power to make new decisions on the land is greatly needed. Ownership grants power to decide. Is there any other way?

Recently, a food system reformer I respect lamented about the ineffectual incremental reforms offered by food philanthropy:

“If there is ONE thing I’d ask of funders, foundations and philanthropists who want to support a transition to agroecology and regenerative farming, it’s this. BUY LAND! There is so much uncertainty to resolve, but nothing happens without land.”

There is a tendency for food system reformers, frustrated with a lack of progress, to reach towards the power guaranteed through of land ownership. The sentiment suggests: If only the “right” kind of philanthropic interests owned farmland, then we could have the permission to make land use changes towards sustainable agriculture.

I get it. The power of property is real and it makes sense to want to have that power on the side of sustainable farming rather than industrial agriculture. But this is a trap. I see the very mechanisms of a strong ownership model of property as inevitably intertwined with the types of agricultural decision making that have led us to our state of social and ecological breakdown. So what should we do instead?

This line of thinking inspired a recent talk I prepared for the Food Law Conference at Wageningen University. Here is a loose transcript of the talk with some of the slides.

Food Law talk May 2023 Wageningen

Here is the big picture message of the talk. Systems of land tenure, or the set of formal and informal rules and practices that govern access to land, strongly mediate land use. Land tenure shapes who controls assets, the flow of benefits from the land, and the logics of decision making within the boundaries of a property.

With regards to transformation to a sustainable food system, we have a strong evidence-base and democratic mandate to change land use. I think our notions of appropriate agricultural land use is very contested and dynamic at the moment.

However, our notions of land tenure appear “settled.” They are normalized, epistemic, natural, common sense. And, many places in the “minority world” or wealthy countries, an “ownership or Blackstonian model of property” made up of layered legal entitlements and social norms continuously construct a very homogenous land tenure situation.

This is a problem, because if our interventions into land use don’t involve equal attention to changes to land tenure, our attempts at sustainable food transformations will graft onto the existing power of the property regime, rendering our reforms either 1) inequitable or 2) ineffective.

So when I look at a broad level at some of key objectives of policy ambitions like European Green Deal or the Farm to Fork strategy, I am very impressed by these land use targets. But I am deeply worried about the lack of a willingness to propose changes to land tenure.

A reason for this is the way property entitlements are intertwined with state authority. Rules of property are created when contests over some benefit flow or resource, result in some groups making an appeal to authority. The authority could be moral, religious, cultural, a threat of violence, perhaps, but also, most importantly, claims seek authority from a political-legal institution. The action isn’t one way, however, as state institutions gain power by showing they can validate a claim and resolve disputes. Legal geographers, like Sandy Kedar suggest this action of states validating property claims is a part of state formation and maintaining legitimacy to govern.

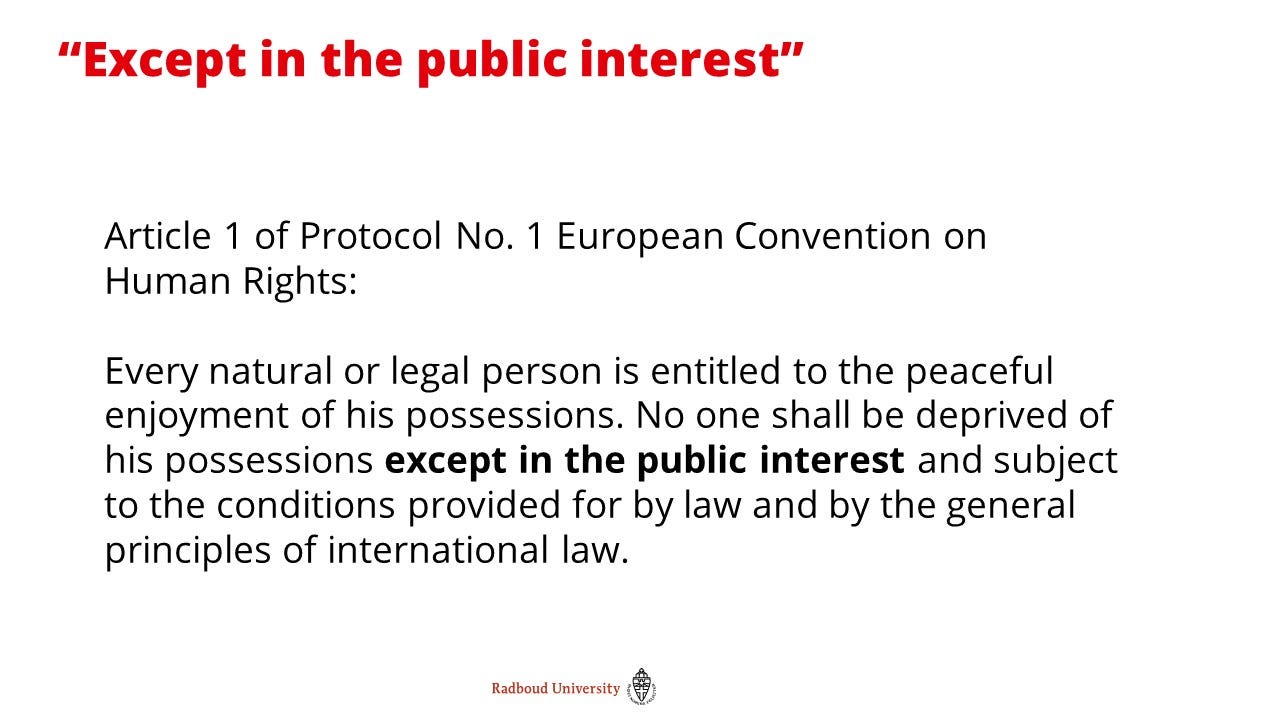

Thus the state has a strong interest in upholding the standard norms of property entitlements, and in Europe, this right to property is equated as a human right. Shaking this up is a direct challenge to the legitimacy of the state itself.

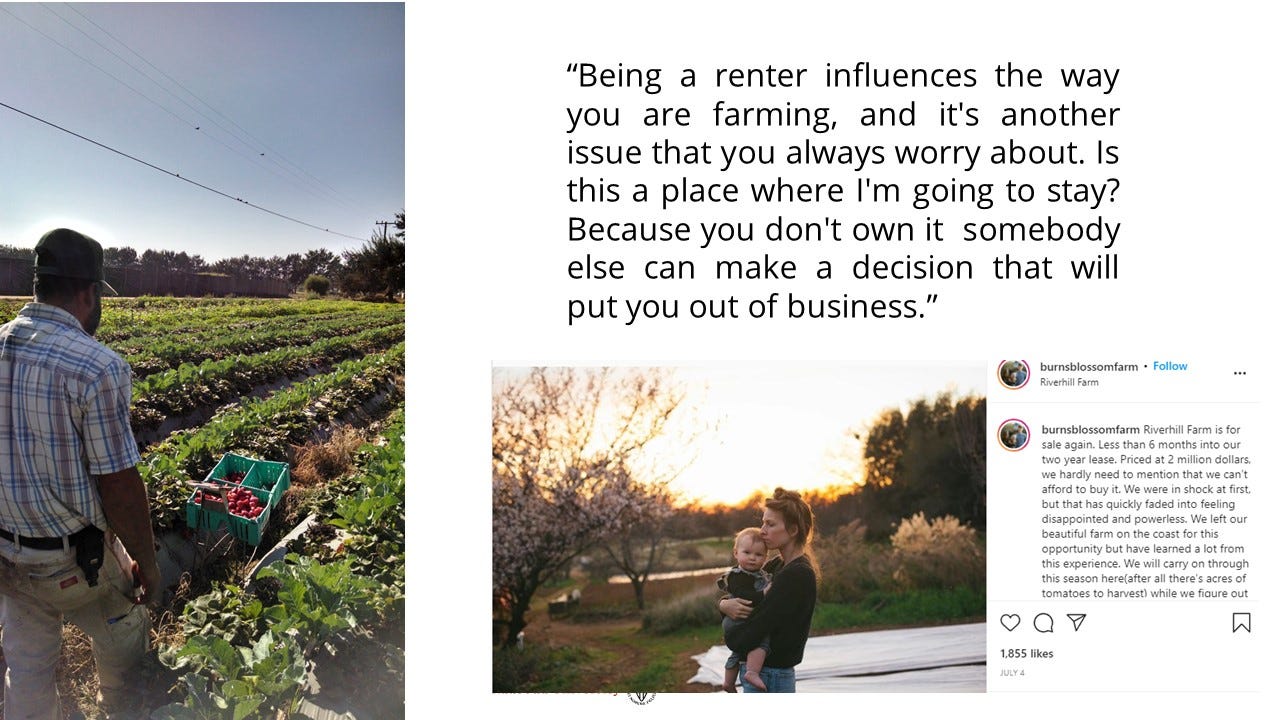

A comment from Sue Pritchard, the Executive Director of the Food Farming and countryside Commission, really highlights the issue of property rights and sustainable food, but also shows how complex it is. Sue says:

If there is ONE thing I’d ask of funders, foundations and philanthropists who want to support a transition to agroecology and regenerative farming, it’s this. BUY LAND! There is so much uncertainty to resolve, but nothing happens without land.

In one sense, Sue’s frustration here is very insightful. In the sustainable food world, we spend outsize attention to the technocratic elements of food system change; The “innovations” like strip cropping, or gene editing, ag tech, permaculture, or alternative proteins, … we place our hopes in these things and thus they are what grab the headlines and empty the pockets of philanthropy and research grants. But Sue’s quote relates a frustration I share:

If the farmers who have the ability to produce high quality, abundant, food in a socially just an ecologically sensitive way don’t have control over land, the technical dimensions of agroecology are a moot point. At this moment, the food system reform movement has a strong technical strategy for change, but does not have coherent asset transfer strategy.

But Sue’s solution to the problem here is revealing, because it represents a failure of imagination. Sue doesn’t challenge the nature of the property regime, but rather just wishes it’s power was redirected towards agricultural actors she prefers.

Property is not a set of natural rules, it has always been a set of social relations established in order to service a certain set of users and a certain set of economic activities. Drawing on critical property scholar Carol Rose, The origins of property are about establishing clear boundaries of control, such that objects within can be managed and traded in pursuit of ‘cultivation, manufacture and development’ to serve a decidedly ‘commercial people’

In the words of Rose:

The metaphor of the law of first possession is, after all, death and transfiguration; to own a fox the hunter must slay it, so that they or someone else can turn it in to a coat.

Thus, to go back to the original message of the talk, if the property regime articulates with a certain logic of production, then the current land use context of unjust and ecologically damaging industrial food system is deeply aligned with the Blackstonian model of property. Placing new owners into this system will not result in transformation.

Let’s look briefly at three dominant ways of thinking about changing land use in the food system.

First, we can try to change the behaviors of the existing owners of agricultural land and food system assets. We can nudge, use market incentives, do voluntary trainings and awareness raising. I won’t spend too much time here other to say that I don’t think this has been effective. The incentives that property regime produce are often much more structural and distorting than the reformist efforts to change behaviors.

Second, we can use regulation to create new rules of land use without reconfiguring property.

Here, the teeth of regulation are innately blunted by the states commitment to property. There is always a tension in a strong property regime, where constraints on land use must not breach the ownership right. And if the proposed regulation does threaten the control over land, you have ripe conditions for political backlash, because such a regulation is at once an existential threat to land control and a betrayal of the original contract between land owners and the state.

Thus, I see the recent conflagrations in the Netherlands over the efforts to reduce nitrogen emissions not as a nature versus farming issue, as it has been framed, but as a more primal struggle over land.

Finally, in three countries I have now studied the theory of change that says ageing farmers will slowly transfer their land to a younger generations of more sustainable younger farmers. Again, the problem of the property regime rears its head. The young and beginning farmers I study indeed have alternative ambitions to farm differently and they have the skills to do so. I find the trope that no one is willing to do the labor of an agroecological food system unfounded.

But, the farmers I speak with often don’t have an alternative vision of property. They still seek the myth of a little plot of land with a house on it, as we all do. These farmers, are then encouraged by state agricultural programs to enter a predatory and impenetrable land market that cannot be aligned with their production vision.

And yes, many ageing farmers don’t have successors, but global finance capital is happily scooping up these valuable farmlands as part of a their portfolios.

So that leads to a fourth, untested theory of change. While redistribution absolutely must be on the table to transform the increasingly homogenous and consolidated industrial food system, redistribution must be accompanied by experimental reforms to the character of property.

Fortunately, perhaps because of the failures of the sustainable food movement in many wealthy nations over the last decades, there are a number of agricultural social movements that are beginning to do just that. Groups like Terre de Lien in France, the Ecological Land Coop in the UK, the Agrarian Commons in the US, and Land van Ons and Kapitaloceen in the Netherlands all pursue the acquisition of farmland in the market, then install agroecological farmers, having gained decision making power over the land through ownership. Most importantly, these groups all offer some form of tweak to the standard logics of private property either installing extremely long term leases, collective ownership models, or other trust instruments as an effort de-commodify that land from the market forever. These efforts are fairly new and small scale, but they clearly show an recognition that sustainable food transformation can only grow in a soil of reimagined land relations.

However, if you recall my understanding of property as an emergent dynamic between authority, power, and access mechanisms, then what is missing is not the grassroots action, it is innovation within the political-legal institutions to situate changes to property as part of the duty to serve the public.

Put simply, there need to be a more creative imagining of land reform as part of the core work of serving the public interest. I’ll end my presentation with the case of the ongoing Scottish land reform agenda, as means of inspiration of how to do this

Scotland has structure of consolidated land ownership with often very large estates owned by one individual with tenants who have poor economic opportunity. Before any legal changes there was grassroots movement of disenfranchise tenants putting the pressure on estate owners to transfer ownership to local communities. In a famous case the residents of the island of Eigg, intervened in the proposed sale of the entire island via a public pressure campaign. And this gave them time to raise funds and shame the cow the owner into selling to the newly formed Eigg heritage trust, which still controls the island to this day.

Years later, a Scottish land reform agenda has been pursued in the government passing a number of laws that mostly aim to support this type of grassroots action. These new entitlements allow community groups to form an entity and register an interest on any asset in Scotland. And, in the right circumstances these groups can assert a first right of refusal to block the sale of land and get he first chance of taking community ownership. In some cases, for example, vacant and derelict land or land use that prevents a communities sustainable development, they can assert an absolute right to buy. So far, these acts have been connected with a wave of community acquisitions.

And as I have argued in a recent paper, these laws could be used more directly for sustainable food production.

The land reform agenda is not finished. The Scottish land commission, a body created and funded by the land reform acts, has proposed a public interest test on the sale of land above a certain value, that would link land use plans with ownership rights. And the language here is very import.

Part of the legal innovation of the Scottish parliamentarians and land reform proponents has been to justify land reform as part of their constitutional commitment to Human Rights and protocols of the European Convention on Human Rights. The strategy, in a general way, has been to legally argue that the right to property is but one of many other human rights that needs balancing. The notion of economic, cultural and social rights, as established by the UN, has been invoked to challenge the primacy of the right to property. This was a key legal maneuver that weakened the common sense of property in Scotland, and opened up legislative confidence to propose a new vision of land ownership as a balance between individual rights and public responsibilities.

I’ll end on a pessimistic note.

If we go back to Sue Pritchard’s comment, that philanthropy ought to buy land for food system change. I actually think that is more likely scenario to address issues in the food system rather than a wave of bespoke and popular land reform agendas. Newly empowered by these calls for environmental sustainability, private capital has new legitimacy to take control of assets and make them green. The result may be a new green land use regime but with even more wealth accrued to minority interests.

Perhaps this is a fair tradeoff to stave off the worse outcomes of climate change and biodiversity collapse? Regardless, without re-imagining land reform as a public good, because our sustainability interventions graft onto the existing private property regime, this green feudalism is a “pragmatic” path open at the moment and thus staring us in the face:

Farmland values rising (again)

Farmland Values Hit Record Highs, Pricing Out Farmers in the New York Times lays out the latest version of a timeless tale: farmland has seen a 12.4% increase between 2021 and 2022. The story then pivots to smashed dreams of the land seekers — the smallholders looking…