An Alibi for Ecocide

Interview with the author of Saving a Rainforest and Losing the World (Landscapes Podcast)

An apparent "success story" of Amazonian forest conservation motivates a 6-years investigation of the land sparing hypothesis. Dr. Gregory Thaler's new book, Saving a Rainforest and Losing the World, reveals a tragic belief that agricultural intensification will solve our problems of enduring extraction of the world's biodiversity.

Episode Links

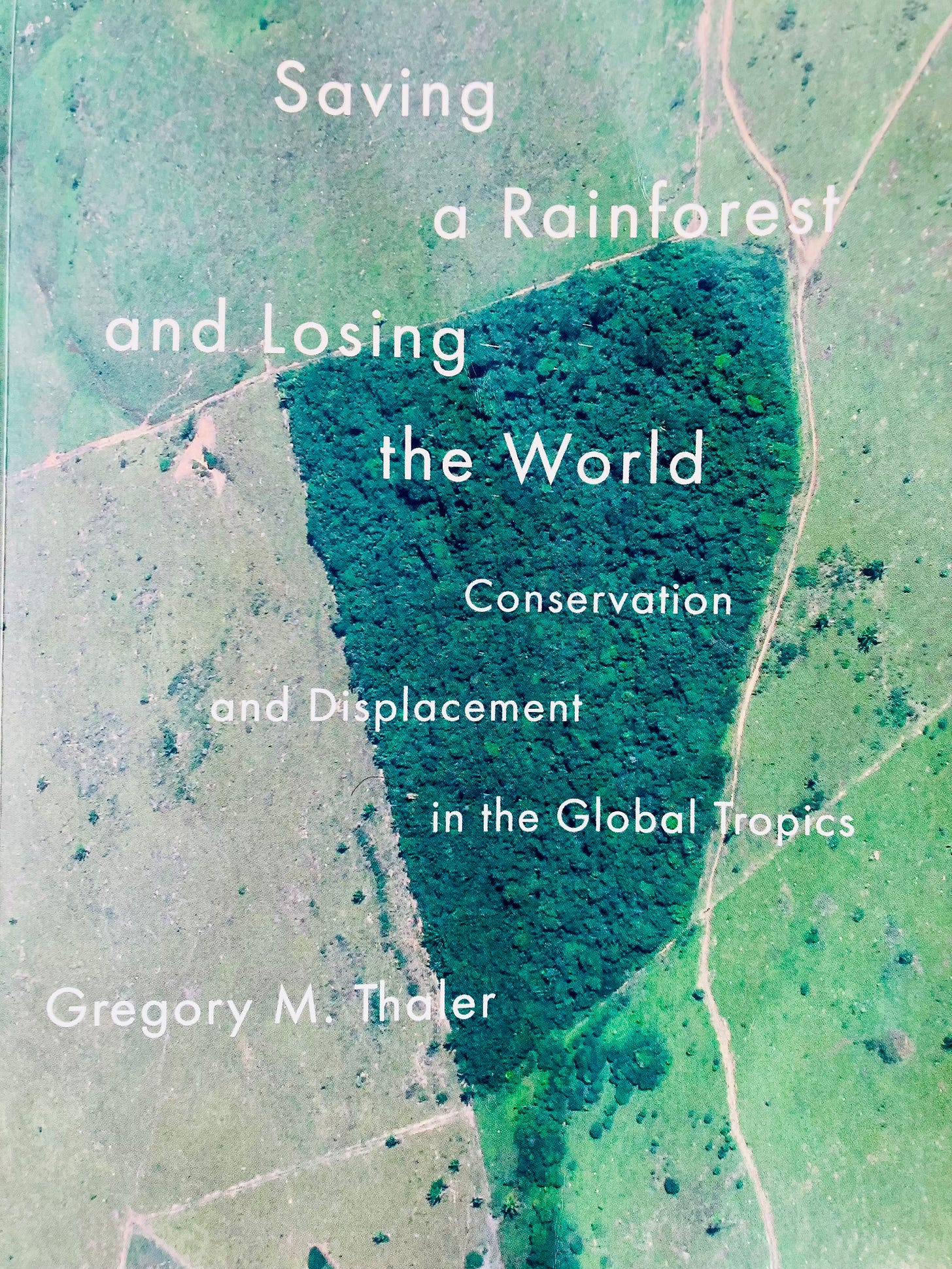

Saving a Rainforest and Losing the World: Conservation and Displacement in the Global Tropics. Yale University Press

Roser, Max. 2024. Why Is Improving Agricultural Productivity Crucial to Ending Global Hunger and Protecting the World’s Wildlife? Our World in Data.

Phalan BT. 2018 What Have We Learned from the Land Sparing-sharing Model? Sustainability. 10(6):1760.

Scientists calling the apparent Brazilian halting of deforestation "one of the great conservation successes of the twenty-first century," in Nature Food

For an excellent review of the Land Sparing / Land Sharing debate see: Claire Kremen, Ilke Geladi (2024). Land-Sparing and Sharing: Identifying Areas of Consensus, Remaining Debate and Alternatives, Editor(s): Samuel M. Scheiner, Encyclopedia of Biodiversity (Third Edition), Academic Press, 435-451, ISBN 9780323984348. OR

Land Spares Feel Their Oats, Land Food nexus

Ritchie, Hannah. 2021. Palm Oil. Our World in Data.

An example of the "active land sparing argument."

The green revolution: Patel, R. (2013). The long green revolution. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(1), 1-63.

An argument for the "forest transition model" as it applies to Brazilian forests.

Landscapes is produced by Adam Calo. Send feedback or questions to adamcalo@substack.com

Music by Blue Dot Sessions: “Kilkerrin” by Blue Dot Sessions (www.sessions.blue).

Introduction

An article titled, Why is improving agricultural productivity crucial to ending global hunger and protecting the world’s wildlife, makes a seductive claim that two birds can be killed with one stone. That is, the twin crises of global hunger and rampant biodiversity loss can be solved with a single intervention: drastically increasing agricultural productivity. The article, written by Max Roser, Program Director of the Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development, writes:

Humanity has just entered a new era: after millennia in which increases in food production were only possible by turning the planet’s wilderness into agricultural land, today, we can increase food production while making more space for other species.

The logic behind this argument revolves around the relationship between increasing production and making “space” for other species. It is an argument that conveniently suggests the solution to the mess we’ve got ourselves in is to make order from chaos. To put human use in one zone, biodiversity in the other.

Such is the dogma of land sparing, a sort of socio technical imaginary that, argues intensifying agricultural production is the most sustainable way forward, because it frees up land for “real nature.” And, in my opinion this idea is having a resurgence.

In the 2010s there was a cloistered technical debate about the merits of the land sparing hypothesis that dominated conservation biology and land use science journals for about a decade. Academic combatants argued to a stalemate, neither accepting each other’s ontological or methodological assumptions. But now, something important is happening: the theory has seeped into the real world.

It’s one thing for ecologists to search for optimality and recommend policy to take up their proscriptions. But what happens when powerful interests that govern some of the world’s most important areas for tropical biodiversity actually adopt the land sparing approach?

At the tail end of the debate, one of the leading land sparing proponents, Ben Phalan wrote:

Critics of land sparing worry that the model could provide ammunition to boosters of industrialised, corporate agriculture, but there is scant (if any) evidence for this.

Times have changed. There is now a ubiquitous din of agribusiness claims that they, once vilified for environmental destruction are actually the heroes of the green transition.

So is land-sparing an evidenced-based recommendation for sustainable food production or a handmaiden to development interests probing for fresh justifications for extraction?

Enter Dr. Gregory Thaler’s new book, Saving a Rainforest and Losing the World, a six-years investigation into the fate of forests at the agrarian frontier of Indonesia, Brazil and Bolivia.

In September Thaler will start as an Associate Professor of Environmental Geography and Latin American Studies in the Oxford School of Global and Area Studies and the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford. He co-directs the Brazil Natural Resource Governance Initiative with colleagues at the University of Georgia—where he was an Assistant Professor of International Relations—and Federal University of Pará (Brazil).

And what does Thaler conclude about the land sparing hypothesis, being promoted today as the key to solving both hunger and biodiversity loss? Thaler says it is “an alibi for ecocide.”

Here is Dr Gregory Thaler.

Interview

*The interview transcript has been edited slightly for comprehension

[00:04:55] Dr. Gregory Thaler: I do work in the Brazilian Amazon and in Indonesian Borneo, and these are tropical humid forests, what we talk about as rainforests.

And these systems are extremely important. Tropical rainforests have received quite a lot of attention in international conservation discourse. And there are a few reasons for that. Humid tropical forests are the most biodiverse terrestrial ecosystems.

They're home to tremendous human cultural diversity. They're vital for the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people on the source of globally traded forest products that are worth billions of dollars, like cacao and acai and Brazil nuts. Tropical deforestation and forest degradation also is a major driver of climate change and tropical humid forests tend to be very carbon dense.

So tropical deforestation in rainforest ecosystems, but also in tropical dry forest ecosystems drives climate change, not just through carbon emissions, but also through changing local and regional temperature and rainfall patterns. And the single largest driver of tropical deforestation is industrial agricultural expansion for commodities like beef and soy and palm oil.

So there's been enormous loss of tropical rainforest ecosystems for agricultural expansion. In the Amazon alone an area the size of France has been deforested and something like 80 percent of the deforested land in the Brazilian Amazon is being used as cattle pasture—so tropical rainforest destruction.

It is a tremendous social and environmental problem and receives quite a lot of attention in international conservation campaigns. Tropical dry forests, as I mentioned, sometimes get overlooked. That's not to say that they're not also extraordinarily important and unique places. So these are still vital ecosystems for endemic biodiversity, for cultural diversity, for carbon sequestration. But they have received often less protection and they may be more endangered even than some of these tropical rainforest ecosystems. And here we can think about, the incredible loss of the Brazilian Cerrado, the tropical savannas in Brazil, about 80 percent of which have been destroyed.

And likewise, the Chaco dry forests in Paraguay, the Chiquitano forest in Bolivia are, these very endangered and, socially and ecologically rich ecosystems. And despite decades of campaigns and policy efforts to try to save tropical forests, over the course of the 21st century, average annual loss of primary tropical forests has increased.

In the first decade of the 21st century, from about 2002 to 2009, we were losing 29,000 square kilometers of primary tropical forests globally in a year. And from 2010 to 2019, that accelerated from 29,000 to 37,000 square kilometers per year, on average, of primary tropical forest destruction.

So this is a problem that's been getting worse, not better.

[00:07:47] Adam Calo: And so amidst these trends, in your book, you start with this hook, that there is this strong narrative of an actual Brazilian forest policy success story. So what is that story that on its face at least appears to show an halting of deforestation?

[00:08:04] Dr. Gregory Thaler: That's right. So in the early 2000s, Amazonian forest destruction in Brazil was accelerating dramatically. That was driven, as I mentioned, in part by cattle ranching, but also by soy expansion. And soy was directly replacing tropical forests, particularly the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, but soy was also pushing cattle ranching further into the forest and indirectly driving new deforestation.

And so there was a great focus of international conservation attention on this rapidly accelerating deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon in the late 1990s and into the early 2000s. In the early 2000s, the Lula government was elected for the first time. This was Lula's first administration as president of Brazil.

He came in with strong ties to environmental movements. The rubber tapper leader, Marina Silva, became Minister of Environment in the Lula administration. And this new government in Brazil launched a suite of policies in 2004, aiming to control Amazonian deforestation. These policies focused on deforestation monitoring and enforcement on creating protected areas and indigenous territories.

They focused on enforcing some Brazilian legal requirements for property owners to maintain a certain proportion of their properties in the Amazon under native vegetation, that's known as the Brazilian forest code. And they also included these incentives for agricultural intensification. So, the idea was that at the same time as policies were going to kind of crack down on illegal deforestation and enforce these requirements for conservation, they were also going to increase agricultural production in the existing cleared areas.

So that both conservation and agricultural development could occur at the same time. And that concept, that idea of more intensive agricultural practices producing more on existing land areas, we can spare, other areas. We can spare forests from destruction. We can spare other natural areas.

That is the idea known as land sparing, this idea that intensive agriculture spares land for nature. So these Brazilian policies that came into place really in the early 2000s after 2004 were an implementation of this land sparing idea on a massive scale, really on the scale of the Brazilian Amazon, a huge territory.

And these measures were, by some metrics were apparently very successful because from 2004 to 2012, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon declined over 80 percent. There was really kind of a broad narrative of success here: deforestation declined dramatically. These policies were apparently, being successful not only because they were protecting the Brazilian Amazon, but also because Brazilian agricultural production in the Amazon was increasing.

There was increasing cattle production, increasing soy production on existing deforested areas. And so there was this narrative that in fact, Brazil had succeeded in reconciling conservation and agricultural development. Not only was this a tremendous success, some people argued, in fact, that this was the largest contribution of any country to addressing climate change because Brazilian carbon emissions were coming primarily from tropical rainforest destruction, or this was one of the largest drivers of Brazilian emissions.

So that reduction in deforestation was a tremendous reduction in Brazil's overall carbon emissions as well. So there was this narrative of kind of climate success, of forest conservation success, of development success, and the argument that Brazil was a model that other countries should follow.

And so, this Brazilian model was then promoted within Latin America and further afield as far away as Indonesia, another place where I've done some work.

[00:12:04] Adam Calo: That's really where it seems like your interest as a researcher picks up. You see this claim to success, but then also the exporting of that success elsewhere as far away as Indonesia. And It seems like that was actually part of the original idea of the research was maybe to compare the forest governance model that was being explored in Brazil and then also trying to compare that to Indonesia.

[00:12:29] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Yes, that's correct. This project began with the idea of a comparison of Brazil and Indonesia. And what attracted me to that comparison, or what helped structure that question was that during this time, after 2004, from 2004 to 2012 or 2014, as Brazilian Amazonian deforestation was declining dramatically and Brazil was apparently being so successful with these land sparing policies at that very same time 2004 to about 2014-2015, deforestation in Indonesia was accelerating quite dramatically. Indonesia is also an extremely important tropical rainforest country, a key place for tropical rainforest conservation, because Indonesia has the third largest area of tropical rainforest of any country, but also has levels of tropical forest clearing that historically have been surpassed actually only by Brazil.

So Indonesia is the second most important country in that respect for overall tropical forest loss. And many of the same actors and same narratives of land sparing that were declared successful in Brazil were also present in Indonesia. So these arguments and policies that were aiming to intensify agriculture and, pair that with conserving forests—I was seeing those in Indonesia as well as in Brazil. That was then a puzzle: Why were these measures apparently successful in Brazil, where we were seeing these dramatic reductions in deforestation, but apparently not successful in Indonesia, where deforestation was increasing dramatically to the point where I think it was in 2012, primary rainforest destruction in Indonesia actually exceeded the loss of primary rainforest in the Brazilian Amazon, which is really kind of a historic shift. But I began to, kind of think about the project differently over the course of a number of years of research.

When I initially set up this comparison between Brazil and Indonesia, I was structuring it as kind of a variable based comparison or controlled, comparative research design, which is something that's quite common in certain areas of the social sciences, like in political science, for example, where I had received my grad training.

The idea in these controlled comparisons is that you can use different cases to control for different variables. And by sort of looking across these cases eliminating different variables, that are common or canceled out across these cases, you can arrive at some conclusion about what variable is causing a particular phenomenon or what combination of variables is causing a particular phenomenon.

So, canceling out different similarities and differences between Brazil and Indonesia, we should be able to arrive at the cause of Brazil's deforestation success, (apparent success) in reducing deforestation and Indonesia's apparent failure to control deforestation through this land sparing model.

And that is initially a quite attractive approach, but there are a few problems with the assumptions behind that approach and what it can actually teach us about a phenomenon that really is extraordinarily complex—and ultimately, as I came to view it and to study it, a global phenomenon of tropical deforestation.

And the first problem is that taking this kind of variable based comparative approach requires case independence. It means that these cases should, in substantive ways important to your question should not be influencing each other. I was really more interested in exploring connections and understanding relations, and it quickly became apparent to me that what was happening in Brazil and what was happening in Indonesia were not actually independent cases, but, really linked phenomena within a much broader global political economy and global set of environmental politics.

I didn't see these as separate cases anymore. I saw them really as kind of connected nodes within a global network and a global historical process. And so I moved from that approach of controlled comparison, variable based approach to, exploring, deforestation in Brazil, in Indonesia, and ultimately also in Bolivia through an approach of relational comparison, which is a geographical approach to comparison that understands and looks at the connections between different places within a kind of broader networks and relations.

The approach looks to understand something like rising deforestation in Indonesia and declining deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon as linked phenomena within some broader historical process. This sort of moment of development and environmental politics that was occurring in the 2000s into the 2010s.

And so. I pivoted to that approach, and started tracing these relations. And that's also what led me from Brazil to Bolivia was following these connections and relations between apparent deforestation success in the Brazilian Amazon and that, contemporaneous dramatic rises in deforestation, not just in Indonesia, but also in the dry forests of the Bolivian Chiquitano.

[00:17:58] Adam Calo: It's so interesting to me because it seems like the strength of land sparing is in its ability to look at case specific issues. These are modeling exercises where you can track how biodiversity responds to an increase in production, for example. But almost in your own research pathway, you start to see that maybe that was insufficient to understand deforestation.

And so, to actually dig into land sparing, how does the rhetoric of the argument really unfold? Could you try your best of putting on the hat of someone who really invokes it as a key tool to reduce deforestation? Can you do your best to steel man how the argument and how we should use land sparing to attend to forest loss?

[00:18:38] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Yeah, I can try. Land sparing is a very, it's a very logical argument. And as you say, it relies on these logical models to promote this narrative of intensified agriculture as both the development environmental benefit. Land sparing advocates will tend to structure the argument around two different potential models of agriculture.

And this has been kind of the classic formulation since the early 2000s of what's been called the land sparing versus land sharing debate. The way this debate got set up and the way it was modeled was as an evaluation of the alternatives between what was called land sharing, which would be a more biodiverse, less intensive, form of agriculture, meaning less, productivity of specific crops per unit of area. What we might associate in many cases with more kind of small farmer agricultural models—perhaps more of a mosaic of land uses within a landscape—versus land sparing, which is the idea that you're going to have some areas of very intensive production where you are really trying to maximize the yield for the areas where you are engaging in agriculture.

And then you're going to have conservation in these other areas. So rather than let's say, kind of a mosaic of more widespread, more biodiverse, but lower productivity, agriculture, you're going to have, areas of concentrated high intensity production coupled with larger areas of conserved natural ecosystems.

These scenarios are modeled then in this argument. What lands sparing advocates will then kind of assess the trade-offs. The trade offs between these two different systems. There have been a number of studies about how different species respond to these different kinds of spaces, for example, the different agricultural models.

Lands paring conclusions come from these studies suggesting that, actually, preserving these kind of higher biodiversity undisturbed, conservation areas as sort of larger undisturbed tracts is going to give an overall greater benefit to biodiversity than having less intensive, but more biodiverse agriculture spread over a larger area, but consequently having, fewer strictly conserved, non agricultural areas. So, it is an argument about, sort of aggregate benefits and trade-offs. And it's an argument that, if we take this sort of landscape scale, we are going to have greater biodiversity when we, intensify our human activities in particular areas and, and conserve larger areas as undisturbed landscapes or undisturbed conservation areas.

[00:21:29] Adam Calo: In Brazil, you make the claim that this ideology or this evidence based advice took hold into national policy, but can you give an example of what that looks like? What does land sparing policy look like in Brazil?

[00:21:42] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Right. So this, this model was applied really at the scale of the Amazon basin in Brazil. Brazil has a national planning area known as the legal Amazon, which covers a number of Amazonian states It's quite a vast region and across this entire region, this sort of federal policy agenda was implemented that specifically aimed both to say create new protected areas, new kind of conservation areas, new indigenous territories, which, also, tend to dramatically reduce deforestation because they're excluding these kind of frontier agricultural actors in principle.

And so the idea is to pair these kind of conservation areas, indigenous territories, and stricter monitoring and enforcement of, regulations against illegal clearing, and to complement that with agricultural intensification, which would come through measures at the federal level, like, say, agricultural credit for, pasture reformation or more intensive ranching.

And for models that that sought to increase agricultural production on existing agricultural areas and a lot of that has focused on cattle ranching because cattle ranching is, as I mentioned, taking up 80 percent of this deforested area in the Amazon, but it would also come in the form of other sort of credits and infrastructural supports for, say, intensive row crop agriculture. That would be soy, corn, cotton, these other major commodity crops being produced in the Amazon region.

So there's this federal level set of policies, but those federal policies really are kind of a framework within which then a number of other policy actors are also engaging and implementing, this sort of land sparing program.

And so that includes state level governments, that includes international funding agencies that includes non-governmental organizations, environmental NGOs. And so I followed some projects of The Nature Conservancy, also some Brazilian NGOs. And we have these examples then, of these environmental NGOs, which kind of classically we think of environmental NGOs, as being very focused on protecting forest areas—which many of them continue to be focused on forest protection. But rather than working in intact conserved forest areas, These NGOs are working in these agricultural frontiers and attempting to support more intensive production as an implementation of this land sparing policy.

So we have groups like the Nature Conservancy or groups like Instituto Centro Vida, (ICV) in Mato Grosso, Brazil, which initially in the Nature Conservancy's case in particular, had an initial focus on protected areas. But in the 2000s, you have the Nature Conservancy or you have ICV implementing these projects, trying to help small farmers produce more cattle on their farms, through pasture reformation, through adoption of rotational grazing and other agricultural technologies.

So it's quite interesting really to see these environmental NGOs that are trying to increase cattle production as a strategy to save forests because they're following this logic that unless we can produce more in existing areas,

farmers will expand and deforest new areas. But if we can help farmers produce more in their existing land, then they will not have this need to deforest new areas to produce more agricultural commodities. This logic was being implemented, not just by the federal government, but really by this constellation of policy actors an, farmers and corporations within the Brazilian Amazon.

[00:25:28] Adam Calo: And so now we have the benefit of hindsight. So if you're looking back from today, if you're just focusing on the national context of Brazil, how does that forest policy approach fare in terms of its stated aims? What's happening with forest policy now? What's happening with these farmers that have industrialized, or at least increased production? What happens to the forests that were slated for protection?

[00:25:50] Dr. Gregory Thaler: There is an extraordinary diversity of experiences with these policies across the Brazilian Amazon, because this is a vast and diverse area. So one of the arguments that I'm making in the book is that it's not enough to just look at the aggregate measures of success as these statistics that at the Amazonian level tell us that we have reduced overall deforestation and we have increased overall production and therefore this model works.

We actually really need to understand what's happening on the ground in different places and how within the Amazon Basin itself, these policies are changing landscapes and changing people's livelihoods and patterns of production. What I find in my field work in these different areas in the Brazilian Amazon … I conducted research in the state of Pará and the Northeast Amazon, in some agricultural frontier areas, also in the state of Mato Grosso, which has been a powerhouse of industrial agricultural expansion in Brazil.

The implementation of this agenda across these different regions is actually quite variable. And so, in some places you see, in particular Mato Grosso, has been a poster child for the success of this land sparing narrative. You see really intensified row crop agriculture, soy agriculture, and the intensification and expansion of soy, has contributed to more intensified ranching within this municipality because, the remaining forest areas are largely in protected areas or off limits at least this period of land sparing policy, were being more effectively protected.

There are some pretty dramatic shifts in terms of the land use and the political economy of particular regions. I think it's important to say also one of the arguments that I'm making is that this land sparing policy is really about quite a bit more than just land use or forest protection.

It is about shifting the political economies of these regions. So land sparing is a strategy for much broader political economic development in a capitalist sense of industrial growth and accumulation. That transformation is something that happens quite dramatically in some areas of the Southern and Eastern Amazon.

I talk in particular about the municipality of Nova Ubiratã, in Mato Grosso, which is a center of industrial soy production and was, as recently as the 1970s, an area of Amazon and cerrado forest. So we see these dramatic transformations in particular regions where deforestation, really declines very substantially and agricultural production increases dramatically, but that experience doesn't hold everywhere.

And so I also conducted research, and I talk in the book in particular about São Félix do Xingu, which is a municipality in southern Pará state and kind of the northeastern Amazon. And in Xingu, there's, much more mixed experience with these land sparing policies. There is this, federal command and control enforcement of regulations and an imposition of fines for illegal forest clearing. But São Felix do Xingu, at the time—2004 and 2007, when these regulations are coming down, is still very much a frontier cattle municipality.

The soy economy that has arrived in other areas of the Amazon had not really arrived yet in São Felix. And there was a much kind of more difficult transition to more intensified agriculture, more intensified ranching. And São Felix actually goes through an extended period of economic stagnation under these policies.

And even within the Amazon region, then we start to observe certain kind of displacement effects as say ranchers from these more intensified industrialized areas in the south engaging in this intensive supposedly green ranching within, say, Mato Grosso state, but then also reinvesting their profits in these frontier areas in illegal deforestation, deeper in the Amazon, perhaps in São Felix do Xingu, perhaps in this area known as the Terra do Meio, this land, in between the Xingu and, uh, and, Tapajós rivers, Xingu and Iredi rivers.

We see really within the Amazon itself a diversity of responses where in some places land sparing looks very successful and other places perhaps not so much. And this conjuncture of declining deforestation and increasing production in, in the Amazon from 2004 to let's say 2012, 2014 then is, is really reversed with the rise of right wing administrations after the impeachment of jma in the Brazilian presidency. Michelle Teer comes in as president with a very kind of right wing government, and has succeeded by Jair Bolsonaro, who really incentivizes a return to deforestation, to a lack of any concern with Amazonian protection.

So we then observe the reversal of those forest protection policies, but not really the reversal of intensive agriculture. So deforestation in the Amazon, then skyrockets under the Bolsonaro administration, but you still have, a number of actors kind of engaging in these, intensive, industrial, uh, soy development, industrial cotton production, corn, there are ethanol plants, there are chicken factories that are relying on soy for feed that are being placed in these areas.

Industrial development continues a pace, but then is paired once again with really rapid renewed deforestation further into the Amazon. So there's really kind of a conjuncture in Brazil where enforcement and economic incentives, but also underlying economic processes led to declining regional deforestation and rising industrial production in some areas. But that was always partial and it never reflected a complete transformation of the economy into one where new deforestation wouldn't be attractive if it became possible.

And in fact, the Bolsonaro administration really kind of showed that this industrial development, while it was happening apparently with lower levels of deforestation in the Amazon, could very readily be paired with high levels of deforestation as soon as policy restrictions were relaxed.

[00:32:26] Adam Calo: Yeah, this was the one of the key findings that I really took away was with the land sparing model, you get NGOs and all these actors, this constellation of actors invested in pumping up the power of the industrial process. In the book, you have these great descriptions of, dusty towns that are now very gleaming grain and meat complexes.

And so you have these new actors which are tied to global capital. And then, if at some point later the deforestation policy changes, you’ve still got that player on the block who is still having this profit motive to continue to expand. That's always the unsettling piece of land sparing that always gets me, is when you're talking about who benefits from such a policy, you're incentivizing a certain type of productivist actor.

[00:33:14] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Absolutely. My argument is that even when land sparing appears to be working as it appeared to be working in Brazil at this time, from 2005 to 2015, this kind of decade of apparent land sparing success, that success is actually an illusion because, yes, in this region, in aggregate, deforestation was being suppressed and industrial production was continuing, But, my argument and what I kind of show through my research in Bolivia is that, what's actually happened is that the extractive, economic processes that were driving deforestation in Brazil are being displaced outside of the Brazilian Amazon into, into the Brazilian cerrado, into the Bolivian Chiquitania. And so these kinds of industrial centers are actually always still relying on these extractive and environmentally destructive forms of economic activity that land sparing tries to eliminate, which it claims, in fact, to eliminate from the economy.

But my argument and what the book shows is that land sparing doesn't actually eliminate these processes. It shifts them to a different area. And so for a time it can appear that you are successfully limiting deforestation. You're increasing agricultural development. But of course, as you just mentioned, at the moment where you relax those protections, you can very quickly again resume environmental destruction in the Amazon, in Brazil, in whatever region you claim to be sparing land.

More crucially and more fundamentally, I argue even when land sparing appears to be working in a particular region, that's because you have displaced deforesting processes elsewhere. So this apparently successful period of deforestation declines in the Brazilian Amazon were paired with, and in fact relied on the continued massive conversion of landscapes, in linked frontiers on the Brazilian cerrado, these tropical savannas, the Bolivian Chiquitania in the dry forests of Bolivia, and elsewhere. At a global level, actually, land sparing, it doesn't work.

[00:35:25] Adam Calo: This really relates to something that I struggle with in mainstream analysis about landscape management in general, is this frequent language of win-wins and trade-offs. It never really quite sits right with me, maybe because the language stems from a financial vernacular. These terms invoke a metaphor of market transaction or simple auction house that doesn't seem to match the ecological context that they're being applied to. Reading your book, you reveal many times that there is some scientific report or politician or conservationist invoking the win-win when discussing the best routes for forest policy. Who is really winning in these scenarios? Who's losing? And what is this language of win-wins and trade-offs obscuring?

[00:36:08] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Absolutely. Yes. That is certainly an uneasiness that I share in listening to these win-win narratives. What are they obscuring? What, what's being obscured by these win-win narratives? And why, why do I feel uneasy about them? Well, what they're obscuring is this displacement that I mentioned.

What they're obscuring is that when you have apparently reconciled say, forest conservation and industrial agricultural development in the Brazilian Amazon, that's been purchased at the cost of displacement, of displacing environmental destruction, say, to Bolivia, to other regions in Brazil. This is a long term historical process of shifting frontiers of so-called industrial, so-called capitalist development and environmental destruction, where some areas, appear to become greener, appear to control their ecological destruction and become these developed green, modernized, centers, while only accomplishing that through the displacement, the outsourcing of environmental destruction elsewhere. So, there are studies demonstrating the Atlantic forest in Brazil, which is an ecosystem that has been, horrifically devastated, on the order of 90 percent of the Atlantic forest of Brazil has been destroyed.

In past decades, there has been kind of a very modest expansion of Atlantic forest area of forest recovery within the Atlantic forest biome. And that's coupled with –the Atlantic forest coincides with some of Brazil's most populous kind of wealthiest areas like Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

And the point that these studies make is that recovery makes it appear as though you have ecological greening coupled with dramatic development has only been achieved through the massive destruction of the Brazilian Amazon. Rather than say, expanding agricultural production, the Atlantic forest, they shifted the agricultural frontiers to the Amazon.

The Atlantic forest recovers, Sao Paulo and Rio get richer, but that's only through the displacement of environmental destruction, and the dynamic of displacement then continues. And that's what I illustrate that then, in this subsequent moment in the 2000s to 2010s, the Amazon is this new region where, okay, now we're going to reconcile development and conservation and we have these apparently green, industrial cities rising in the Amazon, but, that sort of green development is only being achieved at the cost of massive destruction elsewhere.

And this is a global dynamic. This is not something specific to Brazil, specific to South America, specific to the 1700s to the 20th century because there's this period from the kind of initial colonial period where there's a massive deforestation of New England and then great forest recovery, after the 1800s, really during the 20th century, that forest recovery was is pointed to as, as it's talked about as being a forest transition in the environmental literature.

And that forest transition really was purchased through the outsourcing of environmental destruction of deforestation from New England elsewhere as, as these centers of production and consumption in New England came to rely on more distant ecosystems for their inputs. What's being obscured in these "win-win" narratives is displacement.

You're looking at a "win-win" at a particular territorial level, let's say, that allows you to hide the environmental destruction you are outsourcing elsewhere. And so who's winning in these scenarios? Well, who's winning are those who are invested in this status quo pathway of capitalist development.

Those who are benefiting from this economic model, they have vested interests in making claims about the sort of benign, modernizing, positive even, dimensions of this form of development, when in fact, that development is fundamentally dependent on the exploitation of people.

They're relying especially on over exploitation of people in other places and the destruction of ecosystems, ecologies and other places. And fundamentally, ultimately what that obscures is, is alternatives to this kind of industrial capitalist system of development, which is fundamentally a destructive system. But painting it as a win-win scenario in these different moments and places allows you to defer the need for alternatives.

[00:40:43] Adam Calo: Yeah, it's all such a strange language because in the complexity of the ecosystem, it's just describing a game of two players. And when is that the case?

So if this is not the right way to think about it, you do offer a different framework to thinking about the forests and their fates. And you offer up thinking about a way of forest policy as a dialectic relationship between production and extraction. And you add context to this to show how it's these “regimes of production and extraction” that have been shaped by colonialism, by global markets. Can you describe this relationship and what it offers to describe forest policy?

[00:41:22] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Yes. So the way that I argue that we should understand what land sparing is doing and how land sparing sits within the broader system of political economy and ecology is through this dialectic of extraction and production. Fundamentally, capitalist development is a material process.

It relies on material resources and people's labor, and combining, these to produce commodities that are sold for profit. And there is, this profit imperative within capitalism, which, in most cases kind of manifests as a growth imperative as an imperative to be constantly increasing your profits and therefore constantly increasing your material throughput. The resources that you are extracting and transforming and then selling, so that people consume more and you profit more. This is the fundamental kind of dynamic of economic growth under capitalism. There's a geography to this process. There are particular places where profit gets concentrated, where resources are consumed, where energy is consumed, and these are the places that we describe conventionally as being developed. Development in kind of the crudest forms is GDP per capita measures or GDP measures. It's a measure of consumption. So there are these social and technical and political structures that facilitate concentrating resources through industrial production and consumption in particular places that lead to some places becoming more developed and higher consuming.

Broadly, this is what we talk about today as the Global North. Historically, these are kind of the colonial centers. And those centers of concentrating resources and accumulating wealth and consumption rely on, peripheries rely on, historically on colonies, but on areas of resource extraction where people's labor is being exploited, where, ecologies are being effectively cheaply harvested.

And so the wealth of these centers, is depending on … reliant on the impoverishment of peripheries. And this is a classic kind of world system center periphery understanding. But, I would say, to complicate a little bit, that sort of classic center periphery, understanding as a geographical phenomenon by focusing on these regimes of extraction and production as I talk about them or productivism and highlighting how, in at different territorial levels, particular combinations of political institutions and economic interests can incentivize productivist accumulating wealth generating economy or an extractive economy that sends resources and energy elsewhere. I use that framework to do a couple of things.

One is to explain why land sparing policy did not find the same success in Indonesia that it did in Brazil and that's because land sparing is really about an attempt to shift an economy from an extractive peripheral perspective regime to a productivist developmental regime. In Brazil, the goal here was to change the Amazon from a zone of large scale deforestation and low value production to this industrialized productive zone.

And that was achieved to some degree. Of course, still only at the expense of displacement of relying on extraction elsewhere. In Indonesia, these very strong national and provincial and local extractive regimes, as I call them, were very much invested in, the kind of profits that were coming from extracting, let's say timber and value from plantation expansion and coal mining and that value accrues to a few actors within the domestic economy. But largely also it feeds economic growth in foreign places, in Japan, for example, and in the EU. And so there was not in Indonesia a sufficient coalition behind transformation from a peripheral zone of extraction to a productivist center of accumulation, that land sparing was trying to achieve.

So that's part of what this theoretical framework does is it allows me to explain how land sparing plays out in different places. The other thing that it does is it makes this fundamental point that, production and productivism are always dependent on extraction. When you see productivist accumulation, like we observed in the Brazilian Amazon with industrial agricultural growth during this sort of land sparing decade, we need to realize that that growth, that production is still always dependent on displacement. And we can then trace the processes through which extraction is feeding the industrial growth elsewhere. The industrial growth in Brazil is being fed by extraction from elsewhere. That is what took me to Bolivia, tracing the expansion of extracted Brazilian interests across these different forest frontiers.

[00:46:26] Adam Calo: Yeah, you get this sense in the book in the Indonesian case, that these actors who did benefit from the extractive regime, took the NGO's money and played along and then said, no, thanks, I would like to continue extracting. I guess I hear what you're saying. But then, at the core of the land sparing argument is a claim, you associate it with kind of an eco-modernist claim that this relationship doesn't always have to be the case.

I mean, this is what really is a part of the decoupling debate with emissions right? And that's why land sparing often gets connected with sustainable intensification. That why can't we have some way of producing that actually maximizes the product but dematerializes production so it avoids or at least minimizes the extraction.

[00:47:08] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Right, that is exactly the claim and exactly the problem here. Why can't we have agricultural production that doesn't, rely on expanding extraction? We can have that, but we can't have that within a capitalist model of production.

That, fundamentally would be my argument. And that's because the capitalist model of agriculture is geared towards profit. And profits need constantly to increase. So in a non-capitalist system, we can absolutely and we have, really no shortage of examples of really sustainable long term agricultural models practiced by indigenous and traditional communities, small scale farmers,

the world over that don't rely on structures of displaced ecological destruction. The problem is really with the capitalist nature of agriculture and land sparing is very much a proposal embedded within a model of capitalist industrial development. So land sparing can't be separated from a capitalist model of agriculture.

And within that capitalist agricultural model, fundamentally it doesn't work.

[00:48:24] Adam Calo: These arguments really are brought to life in the chapter, “The Country Jumps the Fence.” It really details how capital interests that are evicted from the deforestation moratoriums in Brazil appear to turn up across the border in the forests of Bolivia. So this is this idea of displacement we were talking about, where the appearance of a reduction in extraction only leads to an extraction somewhere else.

[00:48:46] Dr. Gregory Thaler: During this period where Brazil was apparently having great success in reducing deforestation because deforestation was declining in the Brazilian Amazon, agricultural production increasing at the very same time as Brazil is adopting these land sparing policies to crack down on Amazonian deforestation effectively to close the deforestation frontier in the Amazon, Brazilian actors and capital supported by Brazilian government policy, we're flooding into the Bolivian lowlands. So I conducted research in particular in San Ignacio de Velasco, which is in Santa Cruz department in the Bolivian lowlands. And that's a border municipality across the border from Mato Grosso in Brazil, where the course of the 2000s, really after 2005 and especially from 2010 onward, where you have intensifying land sparing policies in the Brazilian Amazon, you have this enormous influx of Brazilian ranchers and Brazilian investors who drive an incredible expansion of the cattle economy, in particular in San Ignacio de Velasco and in this whole lowland Bolivian frontier region, and they are investing and expanding again at the expense of forests. San Ignacio at the turn of the 21st century, I believe it was about 88 percent forested. Over this period from about Ignacio lost an area of forest the size of Denmark.

There was just enormous forest loss coupled with this dramatic expansion of the cattle economy that was driven not only by Brazilian investors, but substantially and importantly by Brazilian investors and Brazilian ranchers. And it's important to highlight these Brazilian connections to really debunk some of these land sparing claims.

Because this Brazilian expansion was still very much linked to the kind of intensive ranching economy that was being developed in Mato Grosso, in Pará, elsewhere in Brazil, and that was claimed to be green, right? And so you have this claim of kind of green industrial ranching happening in Brazil, when in fact, these same actors are buying massive ranches in Bolivia.

They're deforesting huge areas. They are investing in slaughterhouse infrastructure that ratchets up the expansion of the ranching economy. And they're profiting from sales of high tech ranching technologies to Bolivian ranchers and Brazilian ranchers, in Bolivia, in ways that essentially constitute a flow of profits from the deforesting zones of Bolivia to Brazil.

And so the example that I follow a bit in the book, in addition to slaughterhouse infrastructure—which Brazilians have been very invested in San Ignacio de Velasco is, the trade in cattle genetics. That's trade in cattle semen, cattle embryos. That's part of what's called artificial breeding, a technology that increases or is meant to increase ranching productivity and once again constitutes this flow of profits. Ecological destruction in Bolivia to this intensive ranching economy in Brazil that apparently supposedly in the Amazon has become green, but in fact is still, actually really relying on ecological destruction elsewhere.

[00:52:02] Adam Calo: But modern day proponents of land sparing would suggest that there's a difference between passive land sparing, where productivity gains automatically reduces pressure on natural resources elsewhere, right? Active land sparing, that would somehow use governance or some other technique to pair productivity increases with biodiversity conservation. Doesn't an active land sparing approach solve for the problem of displacement that you've just illustrated?

[00:52:28] Dr. Gregory Thaler: It doesn't solve for the problem because active land sparing is never happening at a global level. Active land sparing is effectively what Brazil implemented in the Brazilian Amazon. As I understand it, active land sparing is just the idea that we need positive conservation measures to be paired with agricultural intensification.

And in fact, Brazil was investing heavily in actively conserving these areas that were supposed to be spared, through agricultural intensification. So passive intensification would be the claim that, if you increase agricultural production kind of just automatically without further intervention, you will see less land converted. Active land sparing is the claim that you need to pair those productivity increases with policy measures that that actively conserve the other lands that you're hoping won't be converted to agriculture. That's what happened in Brazil. And the problem with that proposal is that it's still always focused on a particular territory. So what we miss and what is never really happening is kind of a global scale protection of forest lands from conversion that is congruent with agricultural development.

What we have in practice is just a shifting of the deforestation frontiers from one place to another.

[00:53:43] Adam Calo: In the book you write, "Face to face with the ecological destruction of the planet's best preserved tropical dry forests, many environmentalists and policy makers hew stubbornly to a partial variable based perspective.” Why does this variable based perspective persist? Why is land sparing popular?

[00:54:03] Dr. Gregory Thaler: I think it's popular because for a few reasons. One is because it fits the interests of a number of powerful actors. It very much fits the interests of those who profit from industrial agricultural production to claim that there is a pathway for this production to be green. That it's not actually an environmentally destructive production endeavor. So there's an interest in those who are profiting directly from it. There's an interest from a number of let's say environmentalists or environmental NGOs that embrace this kind of eco modernist pathway that are looking for ways to kind of green capitalism to sort of reconcile the ideas of capitalist development with environmental sustainability. And so for them, land sparing fits within this broader set of sustainable development goals that they're trying to pursue. And it's appealing to state actors who are also invested in economic growth and who are responsive to powerful economic interests and who kind of want to make these claims about green development.

Land sparing is very convenient to a lot of existing very powerful interests. And then there's really just a broad cultural or at a more general popular level, a mythology that is ultimately a form of denial, that somehow we can fix things within capitalism without real fundamental alterations in our patterns of consumption and production. And that's broadly easier for people to hear than telling people that they really need to make fundamental changes or that fundamental changes are necessary in the way that we structure society.

So, it's an effective mythology ultimately of denial.

[00:55:56] Adam Calo: What's the role of the Nature Conservancy in this? Knowing their politics a little bit, they have a technocratic view, but they do really care about biodiversity and forests, and so if you're suggesting that this type of intervention isn't going to work, why do they also enroll in some of these logics?

[00:56:12] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Right. Well, the Nature Conservancy is a huge organization and has a lot of internal diversity as well with within the organization, and diversity of opinions among people at the Nature Conservancy about the best pathways with which to achieve these kind of environmental goals. There's a diversity across NGOs and a diversity even within a very large NGO like the Nature Conservancy in terms of the reasons why people might embrace a land sparing argument. And I think some people who embrace these kind of ecomodernist and land sparing perspectives fundamentally do believe them.

They believe that capitalism can be sustainable. That this is a pathway to both conservation and development. And so, this is reflecting their understanding of how things should work. And one of the tasks of this book is to debunk these arguments and to say that, in fact, this is a false solution.

I think there could also be strategic reasons why people embrace these pathways because, they may not necessarily believe ultimately in a global sense, capitalism can be green, let's say, but, there can be arguments that are sort of the Nature Conservancy views itself as pragmatic.

And so I'll use this word pragmatic. There can be arguments of sort of pragmatic urgency or pragmatic conservation that maybe system change would be an ultimate goal or desirable, but in the near term there's a lot of value to looking at ways to reduce environmental impacts to try and temporarily save some places, save some things from destruction temporarily. At least lessen these impacts.

So if we can make things greener, even if we're not making them fundamentally, truly green, slowing the pace of destruction is still a valuable endeavor. My analysis is that well, of course there's a lot to be said for making concrete gains where you're able to in particular places, making certain things less bad.

We need to kind of keep an eye also on the broader system and recognize that fundamentally a model that reinforces industrial production is going to ultimately reinforce ecological destruction. And so we shouldn't be doubling down on an industrial agricultural model, a model of industrial growth as a pathway towards ecological health.

[00:58:38] Adam Calo: Let me run by you then a recent argument that, in fact, we should do that. You talk about that there's this land sparing treadmill. There is for example, an Our World in Data article about palm oil, which is part of the study area in Indonesia. It essentially makes the case that because palm production is so efficient compared to what alternatives there might be, something like a ban or a boycott would be counterproductive, and that the only solution, then, is to increase the yields of palm oil.

The article states, "Palm oil has been a land sparing crop. Switching to alternatives would mean the world would need to use more farmland and face the environmental costs that come with it. A global boycott of palm oil would not fix the problem. It would simply shift it elsewhere and at a greater scale because the world would need more land to meet demand.

What would you say to that argument?

[00:59:27] Dr. Gregory Thaler: This is kind of a classic strategy, a classic discursive strategy of modernization thinkers broadly and ecological modernization thinking. I think that's a bad argument. The reason I think that it’s a bad argument is because it naturalizes the parameter of demand. So that argument takes demand as demand for let's say an international trade in oil seeds as an inalterable condition and then asks how can we meet the demand for globally traded oil crops? And so fundamentally you have naturalized our existing system of industrial production and then said what's the best way to satisfy that? If we open up that parameter and realize that this existing system of industrial production, where there's palm oil and people are consuming all these processed foods that are based on cheap oils.

People are using all these cosmetics that are based on cheap oils. If that consumption is naturalized, then no matter what you do, it's going to be a destructive process to produce all of that demand. But if you say we can shift demand, we can shift the types of consumption that people are engaging in, we can change the kinds of ecological relations that people have, you no longer have to trade oil crops around the world in order to sell people processed food. you can start investing in and producing food in the places where people live, for example. And so, yes, there's going to be a shift in people's consumption patterns.

The modernization perspective is very much invested in this idea that nothing needs to change in terms of people's lifestyles, in terms of consumption, we just need to find ways to more greenly satisfy the really fundamentally unsustainable levels of global consumption.

[01:01:20] Adam Calo: In the book, you use some strong language against the boosters of the land sparing rhetoric. You say that the years of effort to slow deforestation in Brazil is a mirage. That the land sparing hypothesis is false, full stop, and that land sparing is, quote, an alibi for ecocide.

You know, hearing you talk in this podcast, you have a very moderate and mild mannered tone, but I really felt some emotion coming through the language. So when you run by this argument with this language to people who really do believe in an ecomodernist transition, you know, a green capitalist transition, what kind of effect does it have on them?

[01:01:57] Dr. Gregory Thaler: I certainly stand by these critiques and I stand by what I wrote, that the land sparing hypothesis is false within the parameters of capitalist production and consequently that land sparing is an alibi for ecocide.

And when I make some of these arguments about what I understand to be the very fundamental characteristics of capitalism, capitalist production and capitalist agriculture and the need for alternatives, one of the things that strikes me most is that many people have a very limited ability to think beyond capitalist modernity and to take alternatives seriously.

And that's by design. That's by design of our educational systems, by design of broader social and political discourses that try to reinforce this idea that there is no alternative. There's quite a lot that's been invested in making people believe that we don't have any alternatives to capitalism and that we just have to make it work within this system that, has really wrought incredible social and ecological destruction and caused tremendous amounts of suffering and extinction.

So it's really quite amazing the degree to which people will defend a fundamentally very violent and destructive system. And that's in part because alternatives are actively denigrated, are actively erased, are actively hidden. And people, I think, broadly, have a difficulty just kind of conceiving of a world outside of capitalism.

But human beings have been on this planet, modern humans, for hundreds of thousands of years, and capitalism as a political economic system has existed for just around 500 years.

So, capitalism is a very small piece, actually, of human history, and even in these last 500 years and up to today, we still have, so not just from history, but from kind of contemporary anthropology, we have really a plethora of examples of societies living differently. And I think one of the important things is to kind of open up people's imaginations and understandings, both their kind of scientific historical and anthropological understandings, and also their imaginations to realize that there are alternatives and it doesn't have to be this way.

And when we can kind of free ourselves from that mythology, we can actually start to move in directions that begin to move us away from these very destructive processes and towards a better planet. Because fundamentally, and this is the argument that I make in the book and that I'll repeat: capitalism is ecocide.

The capitalist system is premised on this continued material throughput, this continued material consumption. It is premised on the exploitation of energy and of materials. And over its entire history it has caused and continues to cause enormous ecological damage as well as it's influence on enormous social inequality and exploitation also. So capitalism is ecocide. Land sparing is a claim that tries to argue falsely that capitalism can be green. And so that makes land sparing an alibi for ecocide. And I think we have a moral responsibility to be very strong and clear in debunking false solutions when we are facing human and ecological devastation on a planetary scale,

[01:05:21] Adam Calo: I think in the book you did a really good job of really showing how land sparing smuggles in a green veneer of capitalist production or continued extraction. Something I wondered, though, is were you certain that it was land sparing rhetoric here? The model is presented by a few niche ecologists, I mean, it has been a popular theory in academic circles, but when you were talking to these government actors or timber employees or NGO people, were they invoking that rhetoric or were they just caught up in this kind of broader commitment to greening capitalism?

[01:05:57] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Well, part of what I'm exploring in the book and what I think is really significant about what we've seen in tropical forests and in Brazil, in Indonesia and Bolivia is … you describe it as a niche academic concept, which in many ways it is this sort of land sparing versus land sharing debate.

It's something that got kind of formalized around 2005 by some scientists at Cambridge, but land sparing actually is … that sort of formalization of land sparing really just kind of crystallizes a logic that is really pervasive in capitalist agriculture understandings of capitalist agriculture and development.

So that kind of 2005, let's say formalization is a crystallization of arguments made earlier by Norman Borlaug, who's talked about as the father of the Green Revolution, a Nobel laureate, and Borlaug was also arguing that more intensive agriculture production, more productive agriculture was going to be good for the environment.

Ultimately, we can trace these arguments back, I believe, to much earlier in the history of capitalist agriculture, where colonial plantations were argued to be desirable and superior to supposedly destructive indigenous practices because these colonial plantations were more productive, according to the sort of metrics of the colonizers. And they perceived them to be, or really in many cases, slandered indigenous practices as being destructive of forests.

And so that kind of argument that capitalist agriculture can be better and greener is actually a very pervasive one. And so what we saw in Brazil or in Indonesia, or in Bolivia, is the application of this logic at a very large scale in policy. And so yes, in Brazil, actually very clearly environmental NGOs and people in government will say what we are doing is we are increasing production while conserving the environment.

And so that’s fundamental land sparing idea that we're going to intensify agriculture and develop agriculture, be more productive, in a strategy that's paired with environmental conservation, was the implementation through policy of land sparing logics at a very large scale. So this really is something that comes down to the ground.

And I argue that land sparing is actually kind of an emblem or just a dimension of a much broader set of ideas about capitalist development.

[01:08:26] Adam Calo: You write, “The tragic irony of land sparing and other ecological modernization efforts is that even as they seek to curb the ecological ills of capitalist development to save forests, clean waterways, and clear the air, their reliance on industrial growth means they end up pushing environmental costs onto others. They are saving a rainforest and losing the world. Modernizing displacement is thus a political project that relies fundamentally not just on the displacement of environmental and social costs, but also on the deferral of political responsibility.”

Reading lines like this, I did feel that the book debunks, it critiques, in a way that I appreciate, but it didn't really give us a clear framework for thinking about alternatives to green development. Of course, you don't have to solve all of our problems for us. But now looking forward, you've talked about this a little, imagine with me, what would it look like for, for example, a powerful, well funded NGO like the Nature Conservancy or a ministry of environment in a tropical forest nation, or maybe even a governor of a biodiverse rich province to not defer political responsibility? What would it look like to address this dynamic of production and extraction head on?

[01:09:33] Dr. Gregory Thaler: The work of the book, as you say, is focused more on this kind of debunking. I think that's important because we need to \be able to reject false solutions in order to embrace better solutions in order to embrace alternative pathways. And there's a tremendous amount of great work that's being done by communities and by movements and by scholars on theorizing and enacting alternatives to capitalism.

That wasn't my research and not the focus that I adopted in the book. But that's where I think we need to go and where we need to look next. I would expect these approach approaches to come more from the grassroots or from sort of bottom up initiatives in part because actors who are sort of powerful within existing systems tend to have a lot of alliances or vested interests in a continuation of some of these capitalist political economic forms.

But, broadly, for anyone to embrace this, one of the orientations I think is important, and this is where I do sort of end up in the conclusion, is to stop displacing our environmental impacts and to stop deferring then responsibility for the effects, positive or negative, of our livelihoods and to embrace more regional, social ecological systems and systems of production.

So I talk about this under the label of bioregionalism, which is this idea that our production and consumption should be scaled to a particular place and the ecosystems of a particular area. And that makes us more accountable for the effects of our actions, because, for good or for ill, we benefit or suffer from how we engage with the world around us from which we derive our subsistence as opposed to being able to export our impacts elsewhere.

So that's kind of orientation of bioregionalism is something that I think is common to a lot of different movements that are seeking to construct and enact or are already living sort of alternatives to capitalist systems. And one of the directions that I'm moving now in my research, because I am interested in working towards these answers or towards these alternatives that I think are better for people and better for the planet, is a new line of research that I'm working on with colleagues in the US and in Brazil, that is focused on community agroforestry systems in the Brazilian Amazon and trying to understand

how those systems can be resilient and can feed regional economies that are going to be able to adapt to the climate changes and a number of the destructive processes that we've already set underway and that are going to be able ultimately to help build alternative models of development from the ruins or highly degraded conditions that large areas of the Amazon are currently experiencing.

[01:12:22] Adam Calo: Well, with that nod to the bioregional future, I think that's a great place to end. Dr. Gregory Thaler, thank you so much for talking about land sparing and your new book.

[01:12:33] Dr. Gregory Thaler: Thank you so much for having me.